Tropical dry forests are the most threatened forest type in the world¹. They are distributed across Latin America and the Caribbean; less than 10% of them have remained.

A section of these forests is called Seasonally Dry Tropical Forest (SDTFs), alluding to the fact that its canopy exhibits a lush, green appearance in the rainy season, followed by the shedding of the leaves and a “dry” appearance during the dry season. Its native vegetation is well adapted to survive drought, and they are usually formed on some of the most fertile soils on the planet. This explains both how some of the most ancient civilizations in Latin America have evolved over areas of tropical dry forests and why they are so threatened by conversion into farmland: maize, beans, tomatoes, and peanuts have all originated from the tropical dry forests found in Latin America. The presence of valuable timber trees increases the logging pressure for deforestation in these forests.

Figure 1 Seasonally Dry Tropical Forest converted into pastureland (left-hand side) – photo by Skoog

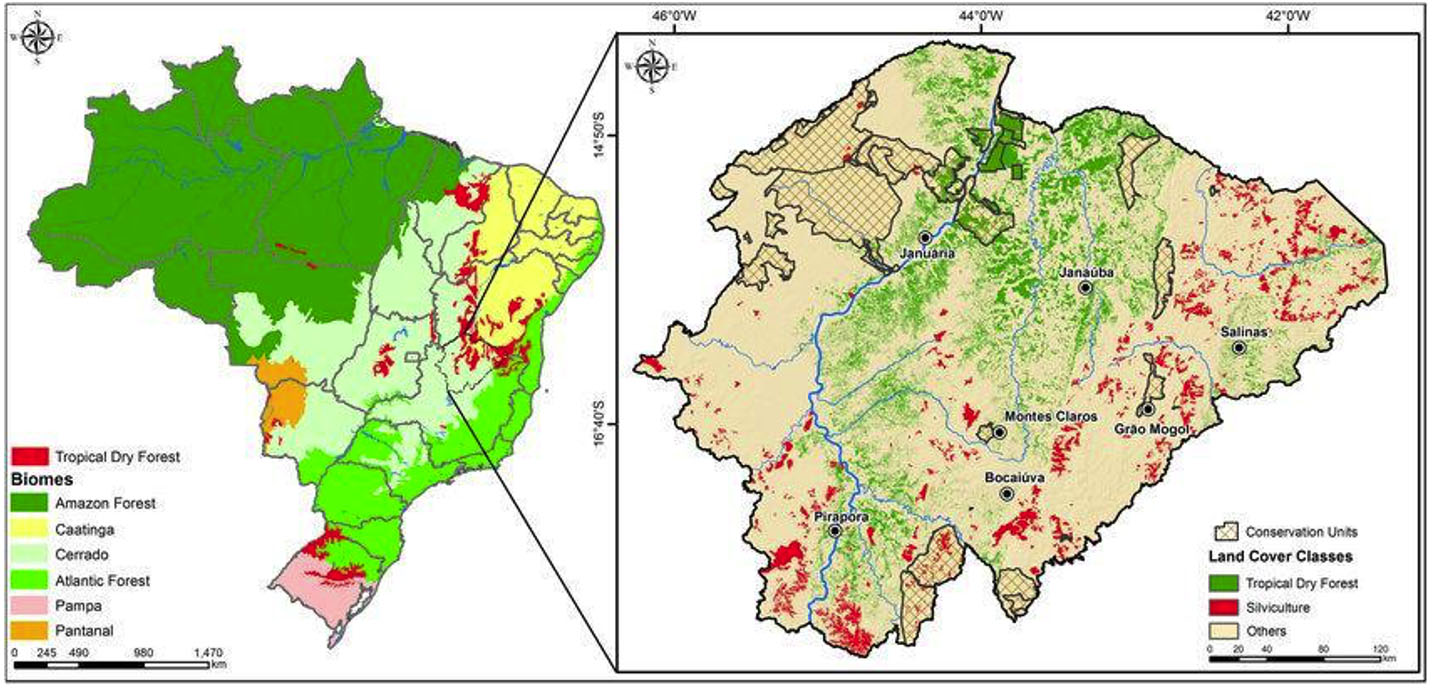

Between 1977 and 2008 in Brazil, two-thirds of this forest was lost, with an annual rate of 3.5% forest cover change. Forest fragments in flatlands have virtually disappeared² and converted into cropland and cattle pastureland. This is particularly noticeable in Northern Minas, Skoog’s initial operating region, which concentrates 78% of the state’s seasonally dry tropical forests.

Figure 2 Location of the north (dotted limit) of Minas Gerais State, in south-eastern Brazil, with its main cities and protected areas. The insertion of this region in Brazilian main biomes and the country’s distribution of tropical dry forests are also shown (IBGE, 2014)

Carbon and biodiversity

Another study³ conducted in the Northern Minas Gerais region highlights that “Although under threat from natural and human disturbance, tropical dry forests are the most endangered ecosystem in the tropics, yet they rarely receive the scientific or conservation attention they deserve”.

Despite the pressure from rural sectors claiming that prohibiting deforestation can hinder economic development and increase poverty, this forest type has “changed” its classification to go under the umbrella of the Atlantic Rainforest biome and be subject to a zero-deforestation legal framework (Federal Decree 750, 1993, and subsequent Federal Law 11428 in 2006). This reclassification has reduced deforestation, although not completely halted it.The study also brings hope: “It has been argued that natural regeneration is faster in SDTFs than in tropical wet forests mainly due to the higher frequency of coppicing in the former (Murphy and Lugo 1986a; Sampaio et al. 2007; Levésque et al. 2011).”. This depends on the land use after deforestation and the potential loss of ecological functions (pollination, seed dispersal, etc.), but the right sites can recover naturally or with naturally assisted regeneration.

Figure 3 An abandoned pastureland (right-hand side) naturally regenerated into a forest, bringing back tree species and water (photo by Skoog)

In the carbon world, this is where things get interesting: tree-planting reforestation projects demand upfront capital to acquire saplings, labour to plant and monitor the tree growth, not to mention the risk. Projects often fail to reach the return, both financially and ecologically.

The paper has studied cases of natural restoration in the Northern Minas Gerais region, where pasturelands abandoned for 12 to 50 years have been restored into secondary forests and turned into conservation areas. This provides insight into the three stages of restoration:

- Early stage: sparse patches of woody vegetation, shrubs, and herbs, with a single vertical stratum formed by a discontinuous canopy approximately 4 meters high.

- Intermediary stage: The intermediate stage has two vertical strata:

- The first stratum is composed of fast-growing trees, 10–12 m in height, forming a closed canopy, with a few emergent trees up to 15 m in height.

- The second stratum is composed of a dense understory with many lianas and juvenile trees juvenile trees.

- Late stage: This stage also has two vertical strata:

- The first stratum comprises tall trees, forming a closed canopy 18–20 m in height.

- The second stratum is a sparse understory with low light penetration and a low density of juvenile trees and lianas.

Figure 4 Forest structural characteristics (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) along a successional gradient in the Mata Seca State Park

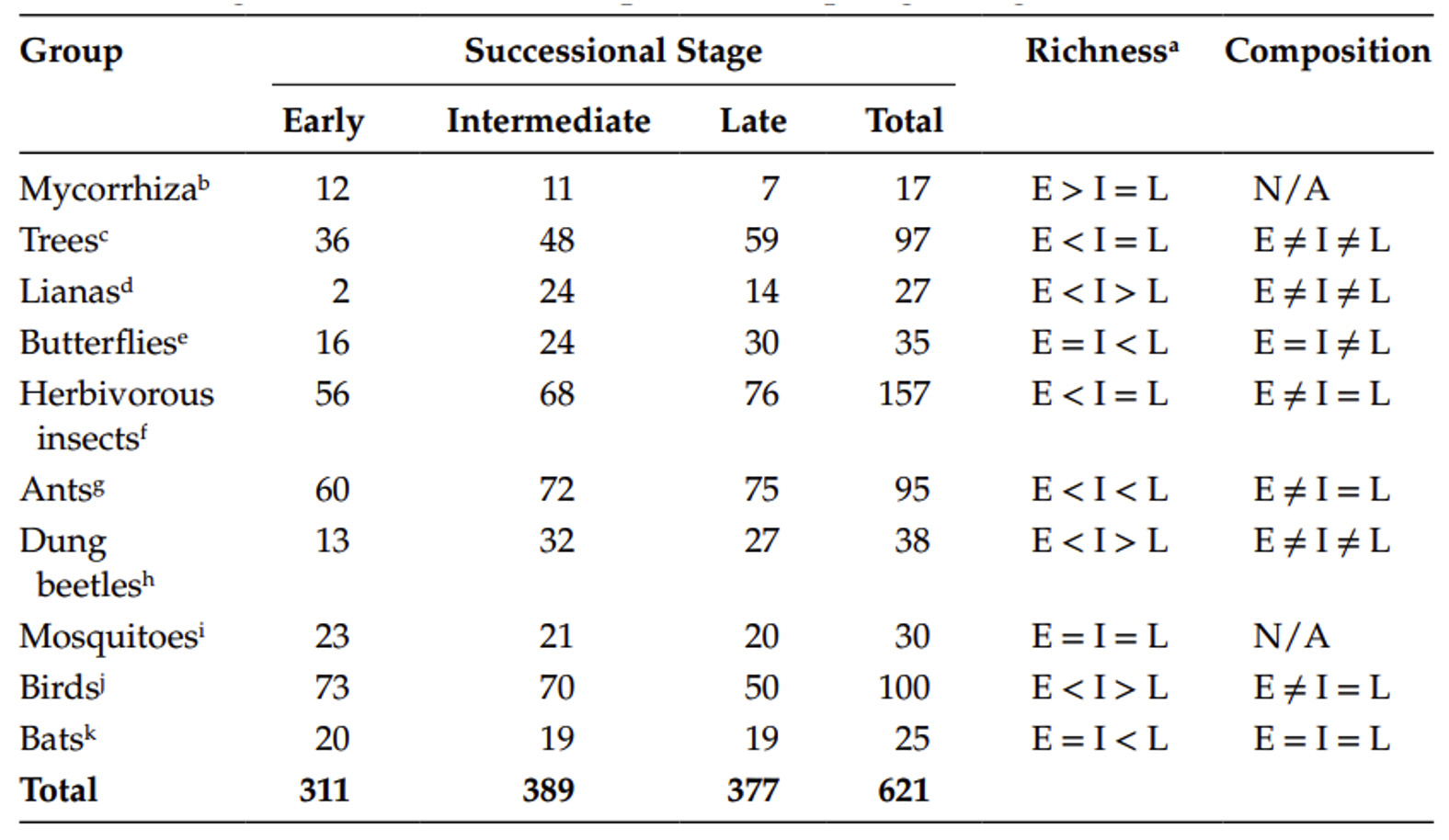

Not only have trees returned, but the study has also inventoried the richness and composition of fauna and flora species over the stages of restoration, showing an increase in biodiversity as the ecosystem was re-established.

Figure 5 Successional Trends for Accumulated Species Richness and Composition for 10 Groups of Organisms Collected in the SDTFs

I have a forest, now what?

Due to the regulations around SDTFs, once a forest of this type is restored, it can no longer be deforested. But there are natural gifts that await discovery..

Aroeira is slang for something of quality in the Northern Minas Gerais region. It is derived from the valuable timber of the Aroeira (Myracrodruon Urundeuva) tree. But this tree has increasingly been used for bee keeping: a study⁴ analysing the properties of different types of honey has found that the Aroeira monofloral honey displays the best results in both phenolic and flavonoid contents and antioxidant activity. The phenolic properties are one of the extraordinary adaptations of this tropical dry species: The plant needs to produce large amounts of phenolic compounds to protect itself by being continuously exposed to extreme temperature conditions. By sucking the plant sap, the aphids induce the tree to produce these phenolic substances, which are excreted by several organs, including the nectaries and flowers. As the phenolic compounds can protect the tree, they can do the same for our bodies. Aroeira honey can boost the human immune system, as well as act as a bactericide and fungicide. Some people also use it to treat gastritis and other inflammatory conditions.

Figure 6 The Aroeira tree (João Medeiros, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

This honey has recently received a DO (Denomination of Origin) and is considered a superfood sold for a premium, offering a very lucrative opportunity for landowners, who many times consider the presence of tropical dry forests as a liability: with low technology, operating expenses, and initial investment costs, the activity can generate profitability between 55-65% ⁵ and reaching 70% to 80% for the Aroeira Honey premium. This opportunity is making cattle ranchers, who are aware of this option, turn into beekeepers. The worldwide demand for honey is rising – combined with a drop in the number of bees available and, hence, the ability to increase supply – making honey prices go up globally.

Figure 7 Aroeira honey (Forbes)

Value Stacking: restoring the SDTFs

Skoog is initiating a program designed to help the restoration of STDFs in the region: landowners will receive incentives from carbon markets to restore this endangered forest, and an important co-benefit provided by the program to “sweeten the deal” is to help landowners understand and tap into alternative revenue streams from the standing forest economy, such as the Aroeira Honey. Revenues from carbon markets can be crucial to the finance this transition, which would not otherwise be possible due to the opportunity cost/loss of revenue from the current activities, mainly extensive cattle ranching. Once restored, subsequent deforestation becomes illegal, ensuring permanence to the project. By why would anyone do it-cattle ranchers turned beekeepers proved to be the biggest advocates for the standing forest economy!

Restoring nature and providing alternatives to increase and diversify income with the forest economy: Skoog’s vision on how carbon credits can finance a bridge to a future, nature-positive economy.

References

¹ Bianchi, C.A. and Haig, S.M. (2013), Deforestation Trends of Tropical Dry Forests in Central Brazil. Biotropica, 45: 395-400. //doi.org/10.1111/btp.12010

² DRYFLOR et al. ,Plant diversity patterns in neotropical dry forests and their conservation implications.Science353, 1383-1387(2016). DOI:10.1126/science.aaf5080

³ Espírito-Santo, Mário & Leite, Lemuel & Neves, Frederico & Nunes, Yule & Borges, Magno & Falcão, Luiz & Pezzini, Flávia & Berbara, Ricardo & Valério, Henrique & Fernandes, G. & Leite, Manoel & Clemente, Carlos Magno & Leite, Marcos. (2013). Tropical dry forests of Northern Minas Gerais, Brazil: diversity, conservation status and natural regeneration.

⁵ Freitas, Débora & Khan, Ahmad & Silva, Lúcia. (2004). Nível tecnológico e rentabilidade de produção de mel de abelha (Apis mellifera) no Ceará. Revista De Economia E Sociologia Rural – Rev Econ e Soc Rural. 42. 10.1590/S0103-20032004000100009.

⁴ Pena Júnior DS, Almeida CA, Santos MCF, Fonseca PHV, Menezes EV, de Melo Junior AF, Brandão MM, de Oliveira DA, Souza LF, Silva JC, Royo VA. Antioxidant activities of some monofloral honey types produced across Minas Gerais (Brazil). PLoS One. 2022 Jan 19;17(1):e0262038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0262038. PMID: 35045085; PMCID: PMC8769325.