Balancing the impact of existing livestock production can be a win-win for cattle farmers and the environment

Drivers of Tropical Deforestation

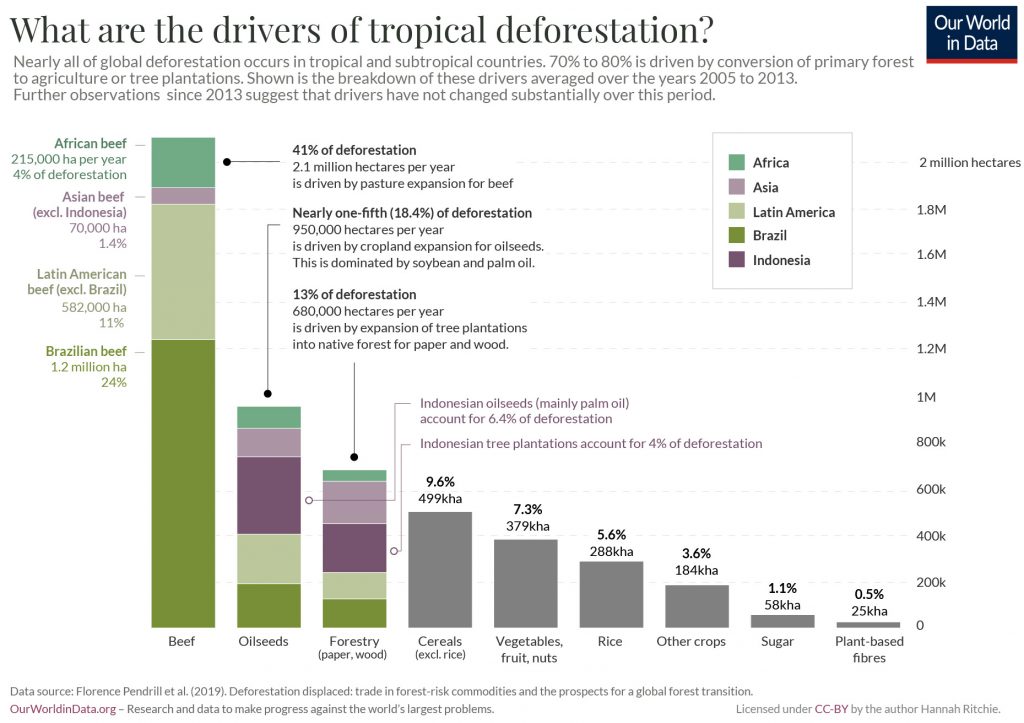

Several studies¹ examined the relationship between tropical deforestation and agriculture, i.e. clearing forests to grow crops, raise livestock and produce products such as paper. Over the years examined by these studies were made, anything between 70 to a staggering 96% of deforestation could be linked to agriculture commodities.

When we break down this information, beef immediately stands out, with one nation taking a clear lead:

Brazil has a long tradition of raising cattle since the 16th century when cattle was brought in, initially to support farming activities such as tillage. This activity spread throughout the centuries in the Southeast and Southern parts of Brazil, having reached the Northern Amazonian region later in the mid-20th century, as mentioned in our previous post with the story of a cattle farming pioneer in the Amazon.

Brazil is now the second biggest beef producer in the world, with an estimated 10.4 million metric tons of production in 2021.

Open Pasture Grazing

Open pasture grazing and extensive cattle farming is the system practiced in very large farms, characterized by low levels of inputs per unit area of land. In such situations, the stocking rate (number of livestock units per area) is low, and there is a clear division between pasture and trees. Expanding this business using this same system hence relies on expanding pasture lands, often through conversion of forest land: clearing up large areas with trees to plant pasture.

A study examining the interactions among Amazon land use, forests, and climate shows extensive cattle farming as the main responsible in virtually every Amazon country, currently accounting for 80% of the deforestation that takes place in that biome².

The Opportunity in Silvopasture

Silvopasture is a form of agroforestry where livestock, trees and forage (grass/hay) are combined in the same parcel. This system creates a “closed-loop” for carbon, with one culture benefiting the other and, if implemented properly, all elements in the system create a symbiotic relationship that benefits both the trees and the forage.

Benefits to move from open cattle grazing to silvopasture systems include diversification of income for farmers, through the addition of a timber element, and improvement of both long and short term productivity of the agricultural operations, through soil health improvement³ and short term improved thermal comfort of the animals⁴, respectively.

A recent study, “Consistent cooling benefits of silvopasture in the tropics”⁵, published in Nature, states that “trees in pasturelands (“silvopasture”) across Latin America and Africa can offer substantial cooling benefits. These cooling benefits increase linearly by −0.32 °C to −2.4 °C per 10 metric tons of woody carbon per hectare”.

With so many benefits, silvopasture is still practiced at a very small share of all livestock farming areas for reasons that include long-term return on investment, perceived complexity, and risk of failure (these systems need to be designed with specific species of trees and grass, spacing between trees and tree rows), etc.

Reducing the Impact of Cattle Farming

Whilst further deforestation of native vegetation must stop, and beef consumption will invariably need to go down, there is a massive opportunity in reducing the impact of existing cattle farming with the transition to silvopasture systems in areas of extensive cattle farming.

Project Drawdown, a non-profit investigating the potential impact of several different climate solutions, highlights that silvopasture is the “highest ranked of all of Project Drawdown’s agricultural solutions in terms of mitigation impact, though it has received little attention”. It also states, “Pastures with trees sequester five to 10 times as much carbon as those of the same size that are treeless while maintaining or increasing productivity and providing a suite of additional benefits. Livestock continues to emit methane and nitrous oxide greenhouse gases, but these are more than offset by carbon sequestration, at least until soil carbon saturation is achieved.”.

Through a rigorous review of existing scientific literature, it is estimated that silvopasture is currently practiced on 500 million hectares. With an expansion in adoption to between 720.55-772.25 million hectares by 2050, carbon dioxide emissions can be reduced by 26.58-42.31 gigatons, an average annual carbon sequestration rate of 2.74 metric tons of carbon per hectare per year in both soil and biomass, besides the financial benefits for farmers adoption such practices.

Scaling Silvopasture

Looking at the costs, benefits, and risks, besides the cultural aspects of moving from a practice established over centuries, it is clear that scaling this solution will require the right set of incentives, knowledge, and risk mitigation.

Skoog is working with universities, farmers and landowners, cattle farmer associations, and cooperatives while also creating a technology platform that will help scale the knowledge. We combine boots on the ground – a team of agriculture and forestry experts working alongside these stakeholders – and leading technology to scale the knowledge in identifying suitable land and designing silvopasture systems with the right elements to ensure successful implementation and adoption. We generate, certify and commercialize carbon credits related to the additional carbon sequestration, which return to the farmers in the form of financial incentives to shift to these practices.

Combined with our incentives to avoid deforestation and increase reforestation in degraded pastureland, we believe in the balance between conservation, restoration, and a thriving agribusiness that expands through increased productivity using natural solutions such as silvopasture systems.

References

¹ Geist, H. J., & Lambin, E. F. (2002). Proximate Causes and Underlying Driving Forces of Tropical Deforestation. BioScience, 52(2), 143-150.

Gibbs, H. K., Ruesch, A. S., Achard, F., Clayton, M. K., Holmgren, P., Ramankutty, N., & Foley, J. A. (2010). Tropical forests were the primary sources of new agricultural land in the 1980s and 1990s. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16732-16737.

Hosonuma, N., Herold, M., De Sy, V., De Fries, R. S., Brockhaus, M., Verchot, L., … & Romijn, E. (2012). An assessment of deforestation and forest degradation drivers in developing countries. Environmental Research Letters, 7(4), 044009.

² Nepstad DC, Stickler CM, Filho BS, Merry F. Interactions among Amazon land use, forests and climate: prospects for a near-term forest tipping point. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008 May 27;363(1498):1737-46. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.0036. PMID: 18267897; PMCID: PMC2373903

³Karki, Sangita & Shange, Raymon & Ankumah, Ramble & McElhenney, Wendell & Idehen, Osa & Poudel, Sanjok & Karki, Uma. (2021). Comparative assessment of soil health indicators in response to woodland and silvopasture land use systems. Agroforestry Systems. 95. 1-14. 10.1007/s10457-020-00577-4.

⁴ Pezzopane JRM, Nicodemo MLF, Bosi C, Garcia AR, Lulu J. Animal thermal comfort indexes in silvopastoral systems with different tree arrangements. J Therm Biol. 2019 Jan;79:103-111. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2018.12.015. Epub 2018 Dec 12. PMID: 30612670

⁵ Zeppetello, L.R.V., Cook-Patton, S.C., Parsons, L.A. et al. Consistent cooling benefits of silvopasture in the tropics. Nat Commun 13, 708 (2022). //doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-28388-4